Introduction

BYOVD attacks (Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver) have evolved into a serious threat in recent years. Attackers exploit legitimate but vulnerable kernel drivers to execute privileged operations on target systems. What matters here is not which drivers are regularly used on the system, but rather which drivers are supported—in other words, which drivers attackers can subsequently install. A recent blog article by Check Point Research shows that various versions of the Truesight driver are actively being used in the wild for such attacks.

This article explores the technical background of BYOVD attacks: why legacy drivers represent a structural security problem, how Microsoft’s protective measures can be circumvented, and how simple the practical exploitation of the Truesight driver actually is.

Why Old Drivers Are So Problematic

Legacy vs. Modern Signatures

Microsoft has tightened the requirements for kernel driver signatures over the years. A crucial turning point was Windows 10 Version 1607: from this version onwards, Microsoft implemented a new policy that prevents the loading of any new kernel-mode drivers that are not signed through the Microsoft Developer Portal (i.e., directly by Microsoft itself).

This tightening was meant to improve driver quality and security. However, there is one significant exception: drivers signed before July 29, 2015, can still be loaded. The actual structural problem: driver vulnerabilities are patched, but Windows still allows the loading of older, signed versions. This means known and already fixed bugs can be deliberately reactivated.

Details about this policy can be found in the official Microsoft documentation on Kernel-Mode Code Signing Policy.

Microsoft’s Countermeasures and Their Limitations

The Windows Driver Blocklist

Microsoft is aware of the problem and maintains a blocklist for known vulnerable drivers. This blocklist identifies problematic drivers based on various characteristics:

- Authentihash: The cryptographic hash of the signed portion of the file

- Version and Name: Specific version numbers and file names

- Signer Information: Identification via the TBS (To Be Signed) hash of the certificate

This multi-layered identification strategy is designed to ensure that vulnerable drivers are reliably detected and blocked.

The Limits of the Blocklist

Despite these efforts, there are significant limitations:

- Version Diversity: A single driver often exists in dozens of different versions. Not all of these versions are necessarily on the blocklist. Attackers can use older or less widespread versions that haven’t been captured yet. For example, a driver might have a vulnerability in versions 3.0.2 through 3.4.7. Theoretically, all versions in this range should be blocked, but frequently only selected versions end up on the blocklist, such as 3.4.7.

- Blocklist Only Active on Newer Systems: The driver blocklist itself is only enabled by default from Windows 11 (2022 Update) onwards. Older Windows versions, particularly Windows Server installations, don’t automatically have this protection. Given the long support lifecycles of server systems and the fact that some organizations still use Windows 10 or older versions, a significant portion of the installed base remains unprotected against known vulnerable drivers.

More information, including the blocklist itself, is provided by Microsoft here.

EDR Software as Additional Protection

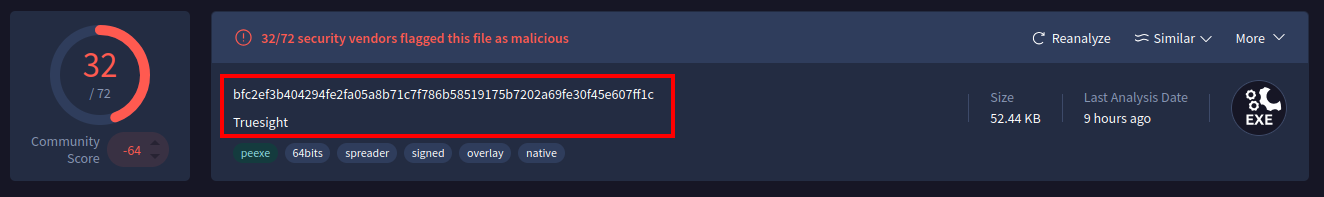

Another layer of protection comes from the deployment of Endpoint Detection and Response software (EDRs). Vendors maintain their own detection signatures for vulnerable drivers actively used by attacker groups. This is evident when analyzing the Truesight driver on VirusTotal:

The scan results can be reviewed here.

Here too, there are limits: CVE-2013-3900 Enables Signature Bypass

Static malware signatures based on hash values can be bypassed by exploiting CVE-2013-3900. The vulnerability allows individual bytes to be modified without invalidating the digital signature (Authentihash). This changes the general file hash, thereby evading detection-based protection measures. This behavior was examined in detail in the aforementioned Check Point article, where over 2500 different variants of the Truesight driver were identified.

When a single byte of the driver is modified, the detection rate drops significantly:

Although CVE-2013-3900 was fixed by Microsoft long ago, a fundamental problem remains: since the fix could potentially cause legitimate, unmodified drivers to no longer load correctly, it is not enabled by default. Instead, it must be manually activated via the registry:

More details can be found on the official Microsoft page. The technical functionality is demonstrated in detail in the following section.

Driver Exploitation Demystified

Less Complicated Than Expected

The term “kernel exploit” sounds like complex buffer overflows, sophisticated ROP chains, and deep understanding of kernel internals. However, the reality of BYOVD attacks is often much simpler: many “kernel driver exploits” are actually trivial functions that the driver provides and that an attacker can simply use themselves.

Anatomy of a Vulnerable Driver

Let’s look at the Truesight driver as a concrete example. Windows kernel drivers follow a standardized structure:

- DriverEntry: The driver’s entry point, called when loading

- IOCTL Handler: A dispatch function that processes incoming I/O control requests

IOCTLs (Input/Output Control Codes) are the interface between userland programs and kernel drivers. A userland process can communicate with a driver via the DeviceIoControl API and send various control codes to trigger specific operations. Local administrator rights are required to load the driver and subsequently interact with it.

A Dangerous Function

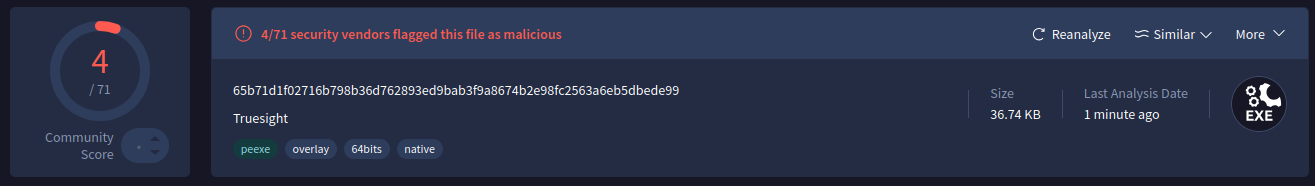

When analyzing the Truesight driver with Binary Ninja, one encounters a particularly interesting function:

This function enables the termination of arbitrary processes via the ZwTerminateProcess() function. A highly privileged operation that is normally blocked even for administrative accounts when dealing with protected processes (Protected Process Light; PPL). Protected Process Light is a Windows protection mechanism that secures security-relevant processes against access attempts, even those made with elevated privileges. EDR products use PPL to reliably protect their security components from deactivation by attackers.

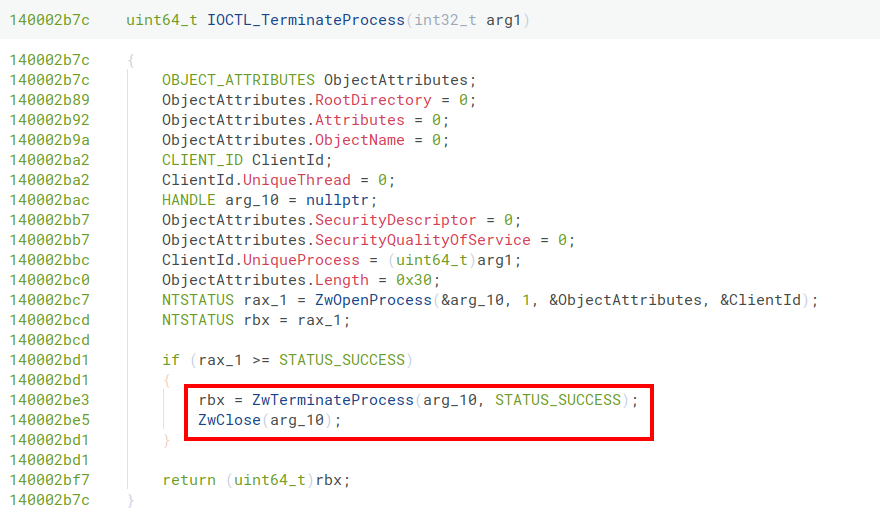

The call graph shows how this function is invoked:

The long switch statement is characteristic of an IOCTL handler. Each case branch handles a specific IOCTL code and executes the corresponding operation. With IOCTL 0x22e044, a wrapper is called that executes the process termination function for any PID. No further filtering or authentication takes place here.

The “Exploit”, Surprisingly Simple

The crucial point is: this is not a classic exploit that exploits a security vulnerability. It is a feature function of the driver implemented by the developers. The attack proceeds as follows:

- Attacker loads the signed legacy driver into the kernel

- Opens a handle to the driver device

- Sends IOCTL code

0x22e044with the process ID of the target process - The driver executes the operation with kernel privileges

- The target process is terminated, even if it’s a system process protected by PPL (e.g., EDR processes)

Simplified pseudo-code for such an attack could look like this:

No buffer overflows, no complex exploits, just legitimate use of an existing driver function with elevated privileges.

CVE-2013-3900 in Practice: Technical Details

CVE-2013-3900 is a vulnerability in the Windows Authenticode verification process that allows certain parts of a signed PE file to be modified without invalidating the digital signature. These areas are not covered by the cryptographic signature and can therefore be modified.

The technical limits: – A maximum of about 10 bytes can be modified, potentially leading to 2^80 different variants – The changes affect the regular file hash (MD5, SHA1, …) – Important: The Authenticode signature and TBS hashes remain unchanged

This allows attackers to bypass typical detection signatures of antivirus programs and EDR solutions, which are based on regular file hashes rather than Authenticode or TBS hashes.

Demonstration with the Truesight Driver

Let’s look at a concrete example. First, we verify the original driver:

The driver is properly signed and accepted by the system. Now we deliberately modify a single byte and check the modified version:

The signature is still valid! A comparison at the hex level shows the modification made:

As can be seen, only a single byte was changed. This minimal modification, however, has significant effects on the hash values:

The SHA256 hashes differ completely, while the Authenticode signature remains identical. This makes it possible to bypass known malware signatures based on file hashes, while the driver is still recognized as legitimate by the operating system. These exact two versions were analyzed via Virus Total as shown in the first part of the blog post. This directly demonstrates the difference in detection rates.

Conclusion

BYOVD attacks demonstrate a fundamental problem in the Windows security architecture: compatibility with legacy drivers creates a persistent security risk. Despite Microsoft’s efforts with blocklists and stricter signature requirements, effective countermeasures remain limited.

The combination of: – Legacy drivers with excessively privileged functions – CVE-2013-3900 for bypassing hash-based detection – Incomplete and not universally activated blocklists

makes these attack vectors an ongoing threat. Defenders should therefore, in addition to activating and updating blocklists, also rely on behavior-based detection mechanisms that monitor the loading of unknown or rarely used kernel drivers.